Most conversations about risk focus on investments — but currencies introduce a different kind of risk altogether: political and structural risk.

Since the start of the year, the U.S. dollar has fallen by almost 10% from its January peak. The decline accelerated after the Trump administration began implementing a broad range of tariffs, shifting how investors view U.S. stability.

Normally, market turbulence sends investors toward the dollar. This time, the turbulence came from within. The policies unsettling global markets were U.S.-driven, and the dollar - usually seen as the world's safest currency - began to lose ground.

Understanding why this matters requires looking beyond headlines and into how currency strength, purchasing power, and global confidence interact.

How a weaker dollar changes purchasing power

A weaker dollar means American consumers get less value abroad. For example, $100 now exchanges for about €88, compared to around €97 earlier this year.

That difference shows up across everyday life. Even if Americans don’t buy foreign goods directly, many products - electronics, vehicles, household appliances - use imported parts. As the dollar weakens, those parts become more expensive, and those costs pass through to consumers.

Tariffs add another layer, raising costs further. Estimates suggest tariffs alone could increase the average American family’s expenses by about $3,800 this year. A weaker dollar amplifies that effect across a wider range of goods, without exemptions.

Why some advocate for a weaker dollar

A weaker dollar can theoretically help U.S. exporters. When the dollar drops, American goods become cheaper for foreign buyers, potentially boosting sales and supporting manufacturing jobs domestically.

President Trump, for instance, openly supported a weaker dollar as part of his push to revitalize American industry.

But the global economy today is more connected than it was decades ago. Even products assembled in the U.S. often rely on foreign components. Higher input costs can offset the competitive advantage of cheaper export prices.

Retaliatory tariffs and shifting sentiment abroad can further reduce demand for U.S. exports, limiting the intended benefits.

The larger risk: trust in U.S. financial stability

Beyond trade, the dollar’s strength reflects global trust in the U.S. economy.

For decades, U.S. Treasuries have served as the world’s de facto safe asset — a place investors could turn to during uncertainty. That trust allowed the U.S. to run deficits and finance spending at lower costs compared to most other countries.

The current environment challenges that dynamic. Policy uncertainty has made investors reconsider the safety of U.S. assets. Some have begun shifting capital toward other currencies and even into gold, an unusual move given that volatility typically strengthens the dollar.

Implications of a weaker dollar on portfolios

A weakening dollar has multiple, sometimes opposing, effects on portfolios, depending on asset classes and exposures.

1. Global equities can outperform

When the dollar weakens, foreign stocks (non-U.S. equities) tend to rise in dollar terms. This happens because when you hold foreign stocks, their local currency returns get translated back into a weaker dollar, amplifying your gains.

Example 1: European stocks returning 5% in euros could translate into a 10%+ return in dollars if the euro strengthens at the same time.

Example 2: Many rupee funds that invest in dollars usually get a boost in returns because of the dollar’s appreciation against the rupee. However, the inverse was true this last month, dragging down their returns.

2. U.S. multinationals can get a tailwind

Companies that earn a significant share of revenue abroad (large U.S. companies or companies with a U.S. holding with a operating subsidiary outside the US) benefit from a weaker dollar because foreign earnings convert into more dollars.

Tracking error in international mutual funds

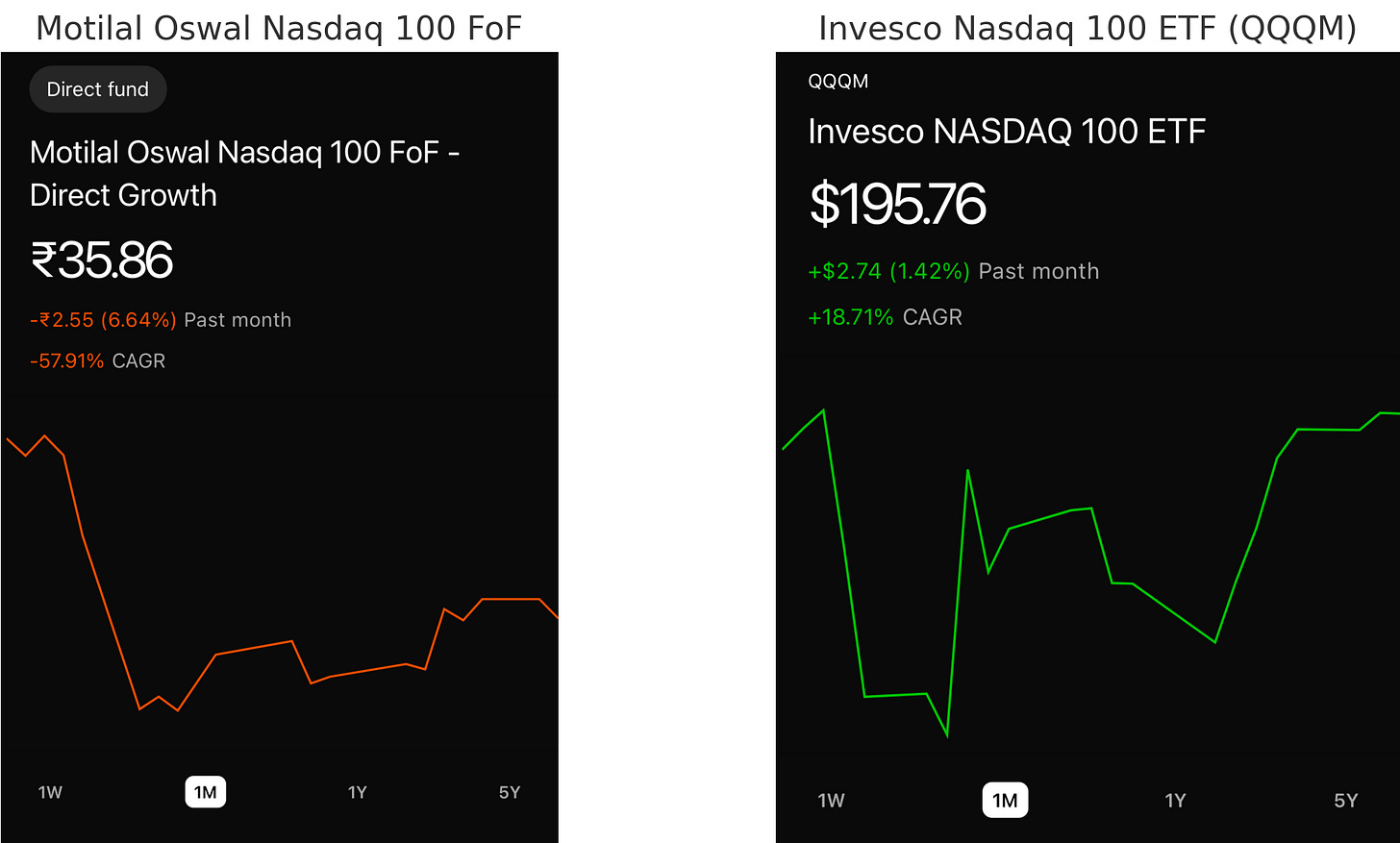

Out of curiosity, I opened the app to compare Motilal Oswal’s NASDAQ 100 Mutual Fund with QQQM, the US-domiciled equivalent.

Even after accounting for currency movement, MOFN 100 is showing a significant tracking error. The issue stems from how it’s managed, not how the index performs.

Indian AMCs have reached SEBI’s $7 billion overseas investment limit. As a result, new inflows into international ETFs/mutual funds like MON 100/MOFN 100 can't be deployed. SIPs are still coming in, but no new ETF units are being created. This creates a mismatch: prices are now being driven by supply and demand instead of net asset value.

The fund’s performance could further drift away from the actual index. Next time when someone asks me why I don’t just invest in MON 100, I’ll just show them these graphs :)

Closing note

While the dollar fumbled, investors flocked, and markets meandered - Vaibhav Suryavanshi struck 100 off 35, epitomizing the true risk tolerance of a 14 year old.

No hedging required.